Period Poverty behind Off-brand Pads

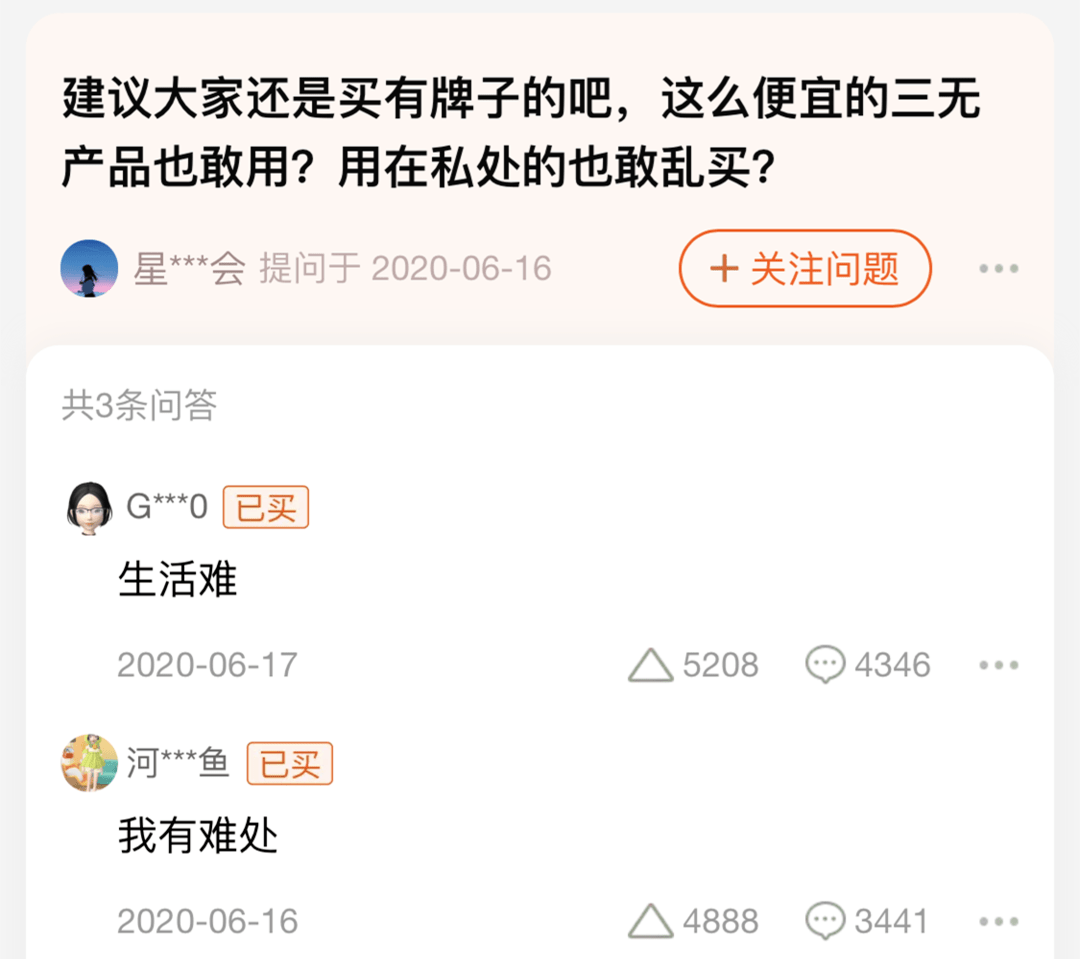

It’s a bargain to get 100 menstrual pads online for $3 in China. Except that these are off-brand products with no outer package. Last month, a screenshot went viral on Chinese social media, capturing the Q&A section between buyers on e-commerce platform Taobao.

Someone asked: “How dare you use such cheap products? How could you buy those for the most delicate part of your body?”

Several formal buyers replied. One said: “Life has been difficult.”

On the product detail page of some cheap off-brand sanitary pads, a user asks why people buy these cheap pads to use on their private parts. The screenshot has gone viral on Chinese social media. (screenshot)

This screenshot provoked a heated debate on Chinese social media. Some people argue that sanitary pads are actually affordable enough. Others disagree, pointing out that as a necessity for women, menstrual products could be a heavy burden on low-income women, especially when they have no choice but to buy them.

More than five million women worldwide are living in period poverty, according to UNICEF data in 2015. They don’t have access to basic menstrual products, hand-washing facilities or a private place to change tampons.

As a result, these women are more susceptible to health risks, more likely to miss school or drop out entirely. In some societies, women face discrimination and even cultural sanctions, just for their periods.

Under the looming COVID–19 pandemic, the costs of pads and tampons can make a huge difference for women who are already struggling to make ends meet. Before the pandemic, they could get free menstrual products from schools, churches or charities, but with curfews, quarantines and social distance restrictions in place, these options don’t work anymore.

For a woman, the period is the “good old friend” for half a lifetime.

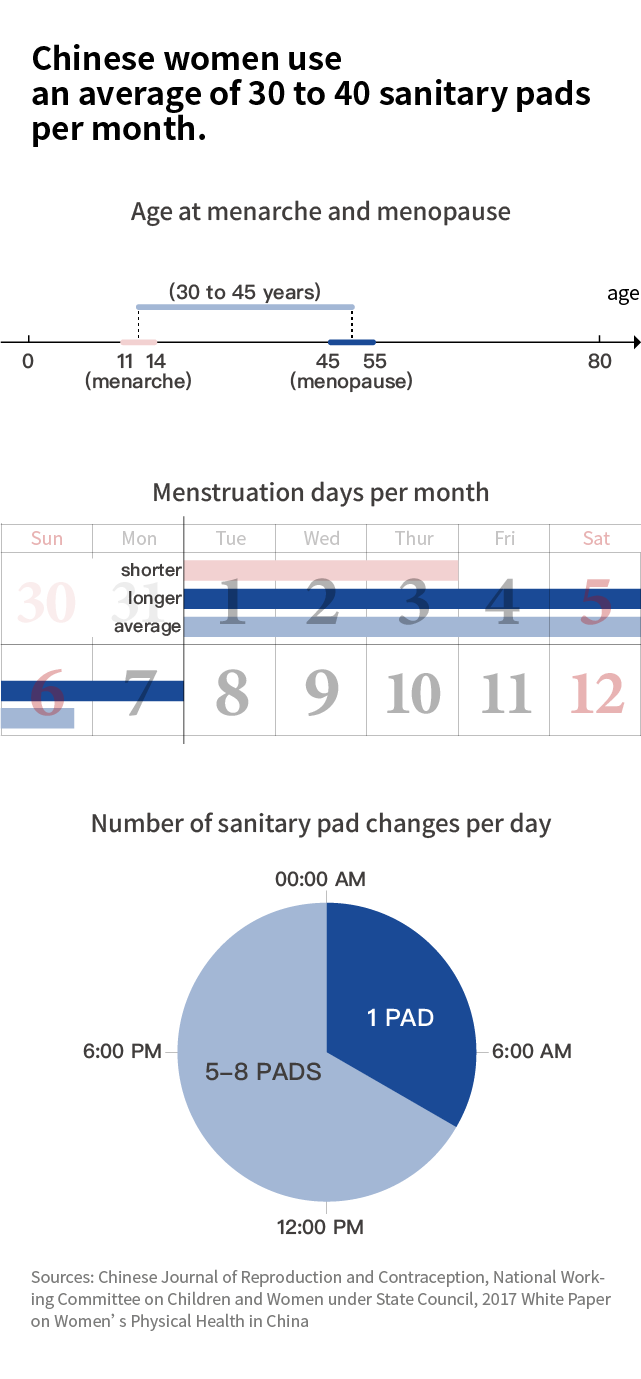

On average, Chinese women have their first period around 13 years old and enter menopause near 50, studies show. Every month, they spend about six days on their period, according to the White Paper on Women’s Physical Health in China. This means an average Chinese woman spends eight years of her life bleeding.

How many sanitary pads does a woman use in a lifetime? How much does it cost?

It is recommended to change pads every two to three hours during the day. Once every three hours, six days a month, from 13 to 50 years old. That equals more than 16,000 pads in total.

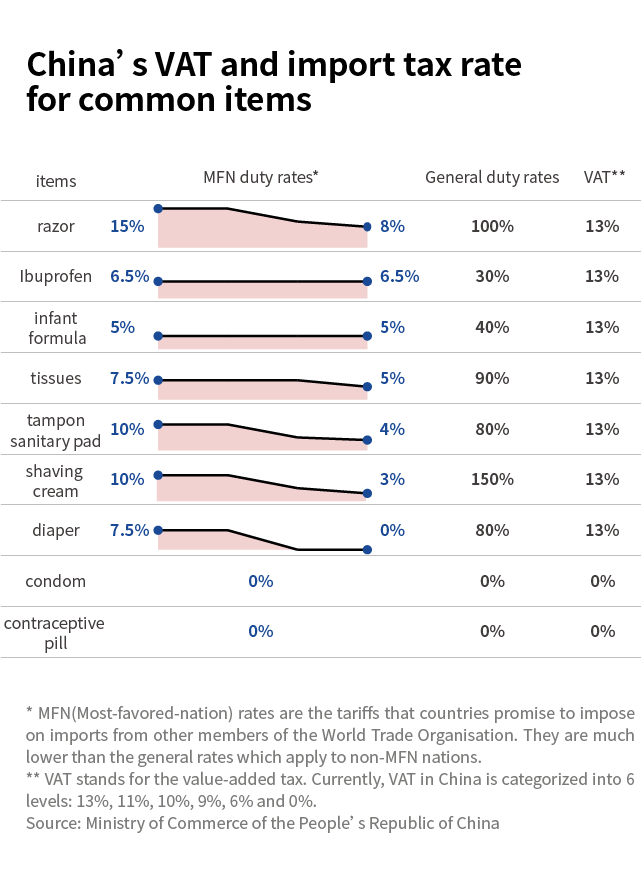

On top of this is the various taxes imposed on menstrual products worldwide.

In 2004, Kenya became the first country in the world to eliminate the tampon tax. India also repealed the 12% goods and services tax on feminine hygiene products in 2018.

In Europe, Ireland is the only country that imposes no taxes on menstrual products. Other EU countries levy taxes at rates ranging from 2.5% to 27%. Germany cut its 19% “luxury tax” on menstrual products to 7% at the end of 2019, now equal to the tax rate of other everyday necessities.

The Chinese government levies a value-added tax (VAT) on sanitary pads, as well as extra duties on imported items. Among items with six levels of VAT rates, menstrual products are subject to the highest rate of 13%. Eight items are exempt from the taxes, including contraceptives, antique books, and imported equipment for scientific research. Menstrual products are not one of them.

Let’s say a woman puts aside 50 yuan (about $8) per month to buy menstrual products in China. How many could she get? How many more could she get if they are tax-free?

Notes: Caixin selected the best-selling tampon and sanitary pad brands on an e-commerce platform as a reference. Prices are calculated without taking into account promotional offers as of Sep. 24, 2020.

In the debate about tax exemption, some people are raising doubts regarding the consequences. Even if the government lifts the tax, will the prices for menstrual products actually drop? Will it benefit the consumers?

Studies show it will. Tax break on menstrual products is fully shifted to consumers and both high and low-income groups benefit from it, according to a study published in the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies in 2018.

After repealing the 6.9% sales tax on menstrual products in New Jersey, the prices dropped by 7.3%. It also benefits low-income consumers more. For high-income consumers, the prices decreased by 3.9%, but for lower-income consumers, the drop was 12.4%. The findings suggested that repealing the tampon tax will make menstrual products more affordable for low-income women.

Period poverty, however, isn’t all about money. It’s also a social justice issue.

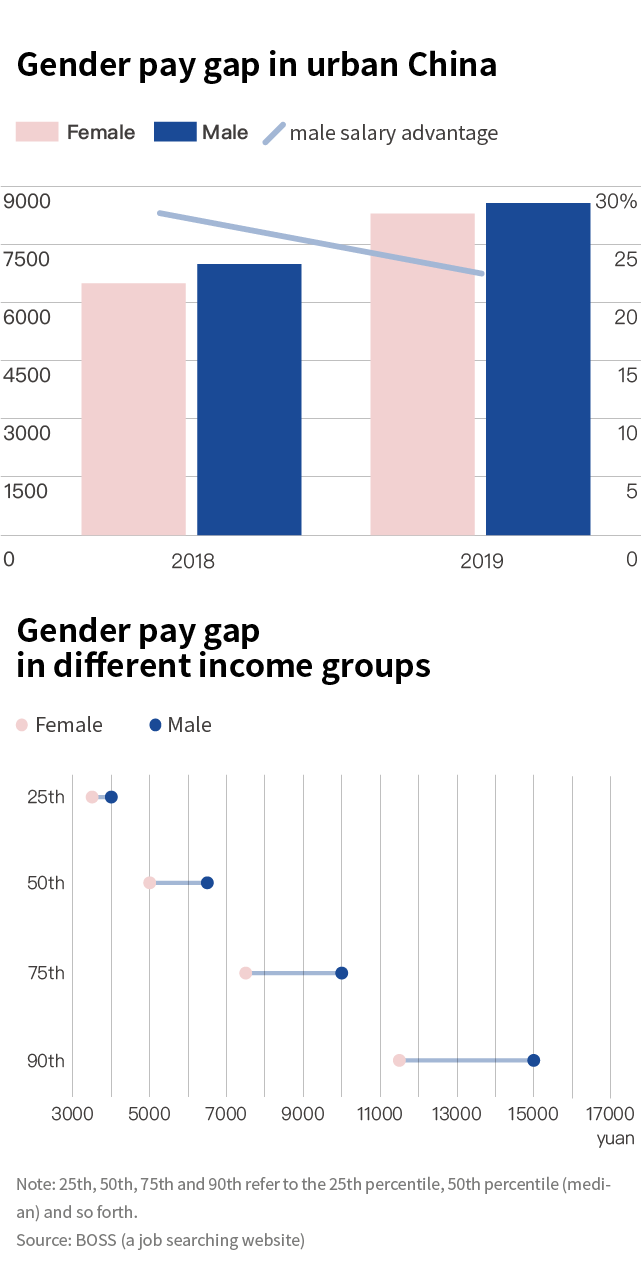

Let’s admit it: Men earn more than women. In China, despite the narrowing of the gender wage gap, male employees’ advantage remains as high as 22.5% and is more significant in the higher-income groups. For women who already earn less, the costs of menstrual products, which are unavoidable, may push them further below the poverty line.

What’s worse, this structural inequality could be perpetuated when girls can’t get an education because they don’t have any menstrual supplies. Many dropped out altogether. In India, this is one of the leading causes of girls dropping out of school. Even in the U.K., more than 138,000 girls missed school in 2017 alone because they couldn’t afford menstrual products.

Before the screenshot went viral, period poverty has hardly been discussed in public. Period shaming is common in China, associating menstruation with filth, disgust and misfortune, rather than a normal biological process. That explains why even women themselves don’t talk openly about female hygiene products, the taxes, or even having cramps.

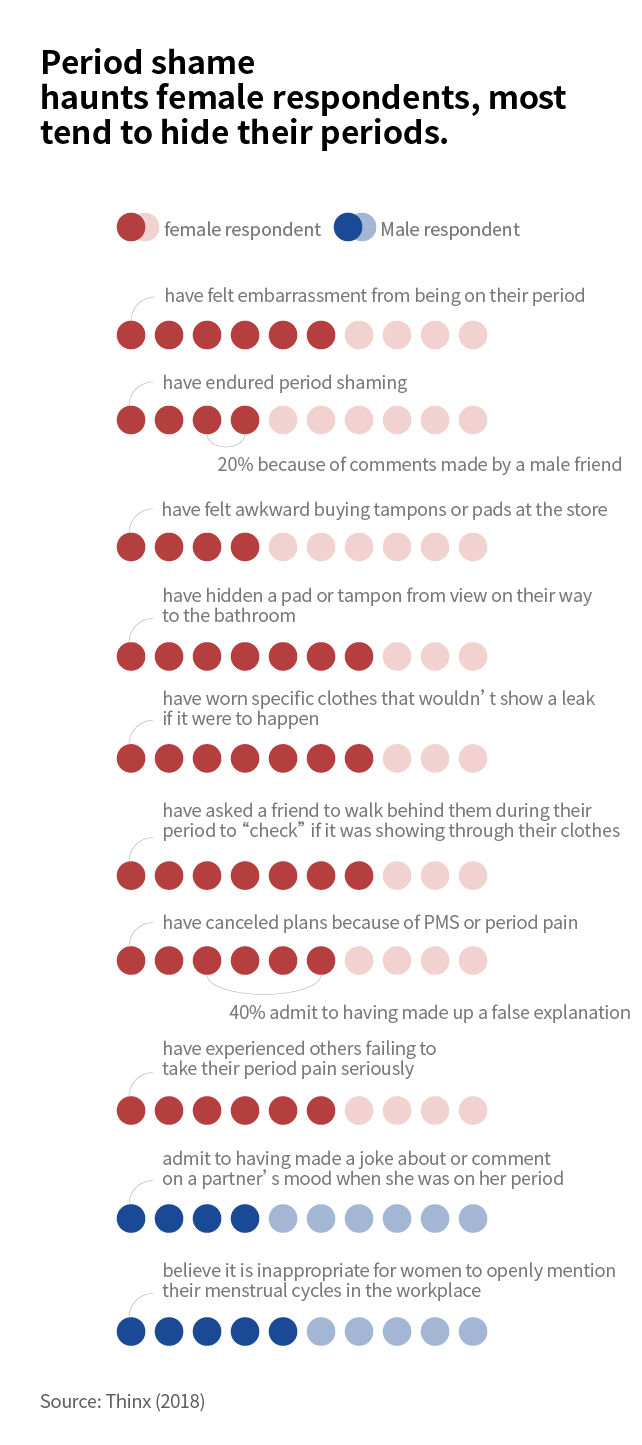

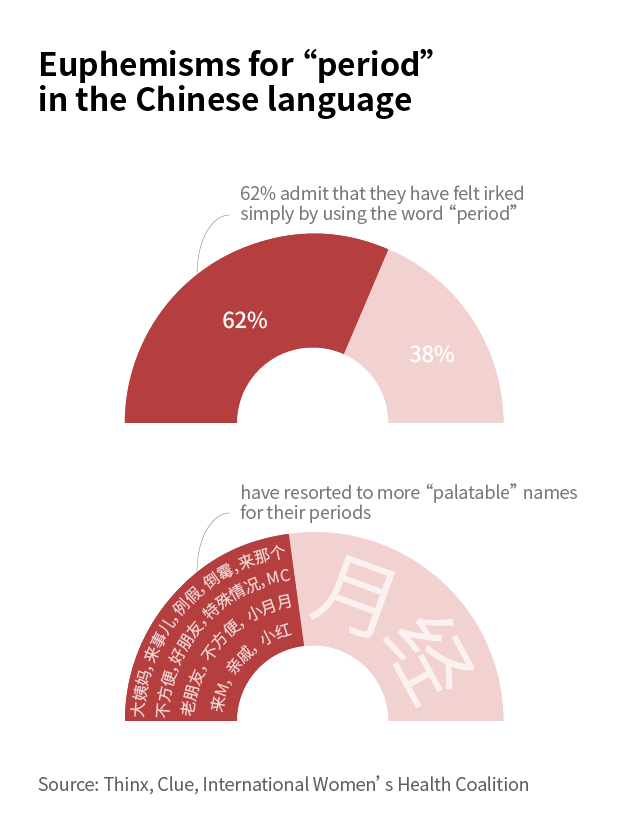

According to a survey by a female hygiene company THINX, about half of the male respondents believe it’s inappropriate for women to openly mention their menstrual cycles in the workplace. In contrast, 78% of the women surveyed have hidden a pad or tampon from view on the way to the restroom. Also, another 62% admit they had felt irked simply by using the word “period."

Another survey collected more than 5,000 euphemisms for the word “period” from users in 190 countries in different languages. In Chinese, “eldest auntie,” “regular holiday,” “that comes,” “bad luck” and “inconvenience” are all commonly used codes for having a period.

Today, the discussions about eradicating period poverty and eliminating the tampon tax seem shaky when people can’t even look straight into someone’s eye and say the word “period” without feeling embarrassed.

Perhaps calling the period by its name would be a good start.

Post a comment